- Report: #652628

Complaint Review: willy farah - orlando Florida

willy farah still ripping people off after all this time orlando, Florida

NOT PRECEDENTIAL

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE THIRD CIRCUIT

No. 04-1017

IN RE: WILLY FARAH,

Debtor

RAYMOND ****

v.

WILLY FARAH; PNC BANK, N.A.

Raymond ****,

Appellant

APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE DISTRICT OF NEW JERSEY

D.C. Civil No. 02-cv-01662

District Judge: The Honorable William J. Martini

Submitted Under Third Circuit LAR 34.1(a)

November 1, 2004

Before: ALITO, BARRY, and FUENTES, Circuit Judges

(Opinion Filed: March 22, 2005)

OPINION

Ten million of these twenty-six m 1 illion dollars appear to correspond with the amount

Farah allegedly withdrew in violation of the investment agreement; it is unclear what the

other sixteen million dollars in claimed damages is all about.

2

BARRY, Circuit Judge

Appellant Raymond **** appeals the decision of the District Court for

the District of New Jersey, which dismissed ****s appeal of a Bankruptcy Court

order as untimely. Because of the unusual circumstances of this case, we will remand to

the District Court with instructions to entertain ****s appeal.

I. Background

**** was a client of an attorney named Ivo G. Caytas. Caytas introduced

**** to Willy Farah, a self-described international business investor and entrepreneur.

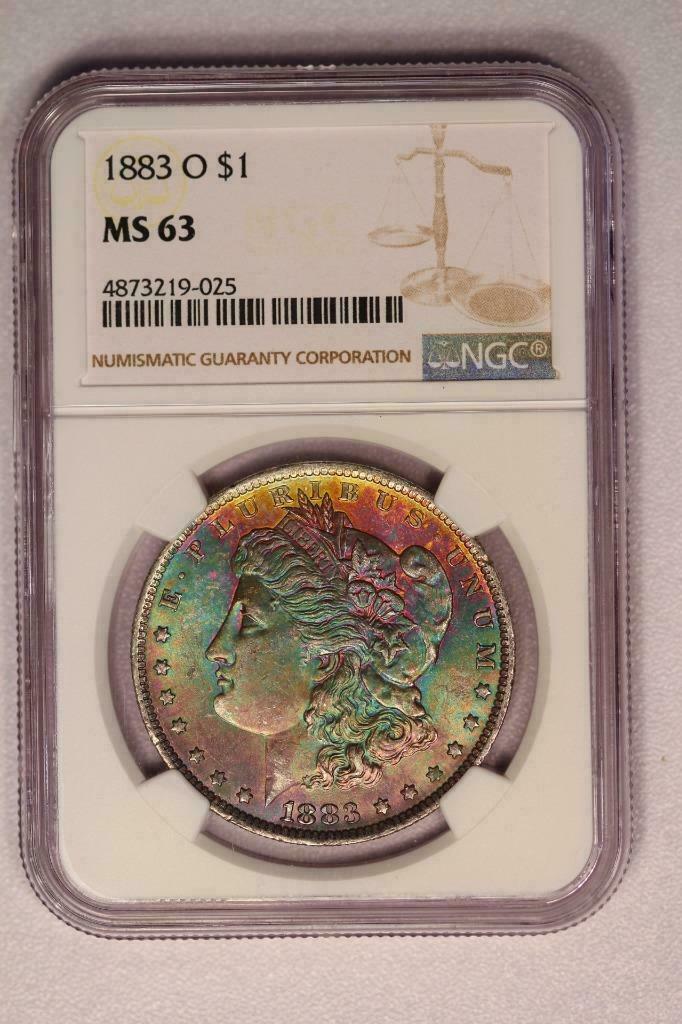

**** became an investor with Farah, investing ten million dollars in a joint bank

account Farah opened at a Mid-Atlantic Bank in Clifton, New Jersey. By 1997, Mid-

Atlantic Bank had become PNC Bank. In the summer of that same year, **** learned

that the funds he had deposited in the account he shared with Farah had been withdrawn.

**** brought suit in the Superior Court of New Jersey.

****s first complaint was in four counts against Farah alone. That complaint,

filed on August 21, 1997, was based on Farahs allegedly fraudulent act of withdrawing

the money from the joint account, and demanded twenty-six million dollars in damages.1

Farah failed to defend, and a default judgment was entered against him on December 11,

1997.

Under New Jersey Court Rule 4:43-2 2, a final judgment by default is a final resolution

of a dispute between the parties involved.

3 New Jersey Court Rule 4:37-2(d) provides that a dismissal with prejudice

constitutes an adjudication on the merits, making it a final determination on the claims

that are dismissed.

4On February 29, 2000,**** filed another complaint against PNC based on

information he obtained through discovery during Farahs bankruptcy proceedings. He

claims, based on this new information, that PNC was negligent in its operation of the joint

account. PNCs motion for summary judgment is pending before the Hon. William J.

Martini.

3

For some reason, five days later the Hon. Jack B. Kirsten, the Superior Court

Judge to whom the case was assigned, allowed **** to file an amended complaint

adding a fifth count sounding in negligence and naming PNC as the defendant in that

count.2 The negligence claim alleged that PNC had allowed Farah to open the joint

account in a way that did not comply with ****s and Farahs investment agreement,

or with customary banking practices. **** sought damages in the amount of ten

million dollars, the amount of money **** had initially deposited in the bank and

Farah had allegedly withdrawn.

On February 27, 1998, PNC moved for summary judgment. The Superior Court

granted PNCs motion on both procedural and substantive grounds, dismissing ****s

complaint against PNC with prejudice on April 23, 1998 (April 98 order).3 ****

moved for reconsideration, but his motion was denied on July 7, 1998. He filed a timely

notice of appeal with the New Jersey Appellate Division on August 2, 1998.4

Backtracking for a moment to May 5, 1998, three months before this appeal of the

4

April 98 order was taken, Farah filed a motion to vacate the default judgment entered

against him. Surprisingly, **** did not oppose Farahs motion. On September 29,

1998, the Superior Court opened the default judgment to give Farah the opportunity to try

to prove a meritorious defense; however, **** could still enforce the judgment, which

had not been vacated. **** began to levy against Farahs assets.

On November 19, 1998, Farah filed a Chapter 11 bankruptcy petition in the

District of New Jersey and, pursuant to 28 U.S.C. 1452, removed all remaining claims

against him, including ****s suit against PNC, to the District of New Jersey on that

same day. The petition and all claims were referred to the Bankruptcy Court.

One day after removal, on November 20, 1998, the Appellate Division dismissed

****s appeal of the April 98 order. The Court stated, without elaboration, that an

appeal of that order would be interlocutory. From this point on, the action shifts entirely

to the federal courts.

Adversary proceedings against Farah went forward in the Bankruptcy Court. On

April 19, 2000, **** filed a motion, under Fed. R. Civ. P. 54(b), seeking review of

the April 98 order based on what he claimed was newly-discovered evidence. The

Bankruptcy Judge, the Hon. Novalyn L. Winfield, denied that motion on June 19, 2001, a

pivotal date in this case. Then, on July 16, 2001, Judge Winfield denied Farahs request

for relief from the twenty-six million dollar default judgment entered against him in

Superior Court in 1997.

5

On July 24, 2001, **** filed a notice of appeal of the July 16, 2001 order in

this Court, in the District of New Jersey, and in the Superior Court, all seeking review of

the April 98 order on the ground that, under Fed. R. Civ. P. 54(b), it was interlocutory

and non-appealable until July 16, 2001. He subsequently moved to transfer the appeal

before this Court to the District of New Jersey, and the motion was granted. ****

withdrew his appeal to the Superior Court.

The District Court Judge, the Hon. William J. Martini, first decided that there was

no jurisdiction to review the April 98 order. **** had argued, and continues to

argue, that he was entitled to an appeal as of right because, when Farah removed these

proceedings, the order granting summary judgment became federalized, pointing to

Tehan v. Disability Management Servs., Inc., 111 F. Supp. 2d 542 (D.N.J. 2000), as

authority. Judge Martini held that Tehan was inapplicable and concluded that Judge

Winfield correctly treated Richardss appeal of the April 98 order, at the Bankruptcy

Court level, as a Fed. R. Civ. P. 54(b) motion. Then, when on June 19, 2001, she issued

an order denying that motion, **** could have appealed that order to the District

Court.

Judge Martini reasoned that the only order **** could properly appeal was one

issued by Judge Winfield. In order to determine whether it was the June 19, 2001 or the

July 16, 2001 order **** had appealed, Judge Martini looked at the issues that

**** had briefed and determined that it was indeed the June 19, 2001 order, which

6

denied the 54(b) motion for review of the April 98 order, that had been appealed.

Having determined what was on appeal, Judge Martini turned to when ****

took that appeal and whether the appeal was timely. A notice of appeal must be filed

within ten days of the order the party seeks to appeal. Fed. R. Bankr. P. 8002(a). Here,

Judge Martini concluded, **** did not file his appeal until July 24, 2001, more than

one month after the June 19, 2001 order.

****s only response to this conclusion was to argue that the June 19, 2001

order did not become final, and therefore appealable, until Judge Winfields July 16,

2001 order and, thus, an appeal filed on July 24, 2001 was within the ten-day window.

Judge Martini found, though, that the concept of finality is more fluid in the bankruptcy

context than it is in the context of traditional civil litigation. Thus, because the June 19

order resolved a discrete dispute, he held that it was final and that ****s July 24,

2001 appeal thereof to the District Court was untimely. On December 3, 2003, Judge

Martini dismissed the appeal. **** timely filed the appeal now before us.

II. Jurisdiction and Standard of Review

This case was properly removed under the bankruptcy removal statute. 28 U.S.C.

1452(a) ([a] party may remove any claim or cause of action in a civil action . . . to the

district court for the district where such civil action is pending, if such district court has

jurisdiction of such claim or cause of action under section 1334 of this title.); see also

Fed. R. Bankr. P. 9027. The District Court had jurisdiction under 28 U.S.C. 1334(b)

In Northern Pipeline Constr. 5 Co. v. Marathon Pipe Line Co., 458 U.S. 50 (1982), the

Supreme Court found the statutory provisions relating venue and removal in bankruptcy

proceedings to be unconstitutional. Just after the Pacor controversy arose, Congress

enacted the Bankruptcy Amendments and Federal Judgeship Act of 1984 in order to

comply with the Marathon decision. That legislation gave the district courts the

jurisdiction that bankruptcy courts had previously enjoyed, and resulted in a renumbering

of the relevant statutory provisions; however, the substance of those sections was not

altered. See Pacor, 458 U.S. at 987 n.4. Specifically, Pacors 1471 is todays 1334;

1478 is 1452; and 1293 is 158.

7

because the Richards-PNC matter was sufficiently related to Farahs case under title 11.

See In re Pacor, Inc., 743 F.2d 984 (3d Cir. 1984) (explaining that related to jurisdiction

depends on whether the outcome of that proceeding could conceivably have any effect

on the estate being administered in bankruptcy.), revd on other grounds, Things

Remembered, Inc. v. Petrarca, 516 U.S. 124 (1995).5

The District Court also acted properly when it referred the case, after removal, to

the Bankruptcy Court for the District of New Jersey. See 28 U.S.C. 157(a). Thereafter,

the District Court appropriately acted in an appellate capacity when it reviewed the final

judgments, orders, and decrees of the Bankruptcy Court. See id. at 158(a).

We have jurisdiction over the District Courts order under 28 U.S.C. 158(d). We

review any factual findings under a clearly erroneous standard, and exercise plenary

review over legal issues. In re Montgomery Ward Holding Corp., 326 F.3d 383, 397 (3d

Cir. 2003); see also Universal Minerals, Inc. v. C. A. Hughes & Co., 669 F.2d 98, 102 (3d

Cir. 1981) (We are in as good a position as the district court to review the findings of

the bankruptcy court, so we review the bankruptcy courts findings by the standards the

It is important 6 to note that the federalization concept has no bearing on the

jurisdiction of the state court vis-a-vis the federal court when a case is removed. This

point is relevant here because one day after Farah removed the case to the District of New

Jersey, the Appellate Division denied ****s appeal from the April 98 order,

deeming it interlocutory. This ruling is a nullity, as the state courts were immediately

stripped of jurisdiction when Farah filed his notice of removal. See In re Diet Drugs

Prods. Liab. Litig., 282 F.3d at 231 n.6.

8

district court should employ, to determine whether the district court erred in its review.).

III. Reviewability of ****s Appeal

As explained above, the substance of Richardss appeal to the District Court was

the April 98 order of the Superior Court that granted summary judgment in favor of

PNC. Properly presenting that issue in federal court was complicated by two concepts:

federalization and finality.

1. Federalization of the April 98 Order

**** has continuously argued that the April 98 order was federalized as

soon as Farah removed the case to federal court. The federalization concept has been

well-established in the non-bankruptcy removal context. See, e.g., In re Diet Drugs

Prods. Liab. Litig., 282 F.3d 220, 231-32 (3d Cir. 2002). This transformation occurs by

virtue of 28 U.S.C. 1450. See id. at 232 n.7 ([w]henever a case is removed,

interlocutory state court orders are transformed . . . into orders of the federal district court

to which the action is removed. The district court is thereupon free to treat the order as it

would any such interlocutory order it might itself have entered.) (internal citations

omitted).6

99

We have not decided whether section 1450 has the same transformative effect

when removal is effected under section 1452, which deals solely with removal in

bankruptcy cases. Nonetheless, the similarities between the general removal procedures

of 28 U.S.C. 1441-46 and the removal procedures in bankruptcy would indicate that

the effect should be the same. Certainly, the Supreme Court has concluded that other

non-bankruptcy removal procedures can comfortably coexist with the bankruptcy

removal procedures. See Petrarca, 516 U.S. at 129. We decline to resolve the issue here,

however, and include this discussion only to indicate that we understand the basis for

****s argument.

2. Finality

Although **** argued in the District Court that he was appealing the

federalized April 98 order, he also argued that his appeal of the Bankruptcy Courts

order of July 16, 2001 was timely and, therefore, properly before the District Court. We

agree with the District Court, though, that **** should have appealed the Bankruptcy

Courts earlier order of June 19, 2001, which denied his motion to review the April 98

order. We base this conclusion on the fact that [a] bankruptcy court order ending a

separate adversary proceeding is appealable as a final order even though that order does

not conclude the entire bankruptcy case. In re Professional Ins. Mgmt., 285 F.3d 268,

281 (3d Cir. 2002). Here, the June 19, 2001 order disposed of ****s claim against

PNC; the July 16, 2001 order dealt with Farahs request for relief from the default

Of course, if **** was appealing a federalized A 7 pril 98 order in se, his appeal

would also have been untimely.

1100

judgment entered against him. Therefore, the clock for ****s appeal as to his claim

against PNC began running on June 19, 2001 and expired on June 29, 2001. See Fed. R.

Bankr. P. 8002(a). Because **** did not appeal until July 24, 2001, his appeal was

untimely.7

Despite this, we recognize some confusion surrounding removal proceedings,

especially in the bankruptcy context. Thus, as we have done before, and given the

circumstances of this particular case, we will do some field engineering in light of the

lack of specificity in the statute about removal of appealed cases [that] poses substantial

procedural problems here for both parties. See Resolution Trust Corp. v. Nernberg, 3

F.3d 62, 67 (3d Cir. 1993). More specifically, because neither the Bankruptcy Court nor

the District Court ruled on the finality of the various orders in this case, including the

April 98 order, **** could not necessarily have known when the finality clock

began to tick. Therefore, guided by the underlying principles at work in Nernberg, we

will deem his June 19, 2001 appeal timely and will remand to the District Court with

instructions to consider the April 98 order on the merits.

IV. Conclusion

The December 3, 2003 order of the District Court will be reversed and this matter

will be remanded for further proceedings consistent with this opinion.

1111